From the first Indigenous peoples to the arrival of Christopher Columbus, through European colonization and the abolition of slavery, Martinique’s history has undergone many upheavals before achieving a measure of stability as a French department in 1946.

Pre-Columbian History of Martinique

Before Christopher Columbus arrived in Martinique on June 15, 1502, the Caribbean island had already experienced several waves of human presence. Archaeological excavations reveal that the earliest traces of human life date back to around 2000 BCE. However, these initial groups were nomadic and did not establish permanent settlements.

Like other Caribbean islands, Martinique’s first true settlement occurred around the 1st century BCE, with the arrival of the Arawaks. Originally from the Orinoco basin—located in present-day Venezuela—the Arawaks brought agricultural practices and a more sedentary lifestyle.

Around the 10th century, a new group known as the Caribs began to gradually expand across the archipelago, eventually settling in Martinique by the 14th century. These populations lived primarily along the coast and sustained themselves through agriculture, hunting, and fishing. Their diet included seafood such as fish, crustaceans, turtles, and manatees.

Arrival of Christopher Columbus

On June 15, 1502, Christopher Columbus landed on the beach of Anse Carbet. Captivated by the island’s beauty, he reportedly declared:

It is the best, the most fertile, the sweetest, the most even, the most charming country there is in the world. It is the most beautiful thing I have seen, so I cannot tire my eyes contemplating such greenery.

Yet for more than a century, Martinique remained forgotten. The Spaniards, deeming the Lesser Antilles unprofitable, showed little interest in the region. It was the French who eventually recognized Martinique’s potential and established a permanent settlement.

Arrival of the French

Cardinal Richelieu, on behalf of King Louis XIII, created the Compagnie des Indes d'Amériques (1635–1650) to colonize the islands of the Lesser Antilles. The conquest of Martinique began on September 1, 1635, with the arrival of a Norman adventurer, Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc (picture on the left). He settled in Martinique with a hundred companions in an area that is now the city of Saint-Pierre, the island’s first capital. Martinique became French territory, administered and operated by a company with a commercial vocation.

At first, the French attempted to coexist with the Carib population, but over time, this shared life deteriorated. The Indigenous people viewed the newcomers with suspicion, as they continued to expand their territory at the Caribs’ expense. Relations became hostile and warlike.

The French wanted the Caribs, who were familiar with the land, to work in the agricultural fields they planned to develop. The Caribs refused to be enslaved in a land they had conquered and defended against the French.

Under the leadership of Beausoleil and François Rolle Loubière, the Caribs were permanently removed or expelled from the island in the late 17th century. Some chose suicide over enslavement by the “enemy” (see Tombeau des Caraïbes, Tomb of the Caribs). Survivors fled to the islands of Dominica or Saint Vincent.

The slavery period

From the end of the Caribs to the abolition of slavery

With the Caribbean decimated, the French settled more on the island. They wanted to take advantage of the climate to exploit certain resources, which would arrive directly at the table of the King of France. This period also marked the arrival of a new population on the island. To exploit the island’s resources, the settlers relied on the Royal Crown to authorize the slave trade from Africa. Following the royal agreement, ships left the ports of Atlantic cities to go to Africa and buy or exchange slaves for European products.

Women were captured to take care of household chores in the masters' house (housework and raising children) or to maintain plantation gardens. Men were responsible for work in the fields. They worked side by side on the sugar cane plantations at the height of the sugar era in Martinique.

Black populations in Africa were expected to withstand the climate better and be more robust and able to endure heavy workloads.

Slavery began in the West Indies as soon as the settlers arrived in 1635. In 1673, the Compagnie du Sénégal was created to deport Black slaves to the islands of the Caribbean and the countries of America. The slave trade became a real market and a constant exchange between Africa and the Caribbean.

Between 1635 and 1789, around 700,000 slaves were deported to Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint-Domingue, the three French colonies in the Caribbean. In 1745, out of 80,000 inhabitants, 65,000 were slaves.

The economy during the period of slavery

Coffee was the first crop exploited. Introduced into Europe by the Dutch, coffee grew rapidly in the colonies. The French established it in their Caribbean colonies (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint-Domingue). They quickly became the world's leading coffee producers. With nearly 50,000 tons of coffee produced annually, they represented more than three-quarters of global consumption at the time.

However, this dominance in the coffee sector did not continue. Indeed, coffee cultivation required costly investments, and fierce competition in Latin America forced settlers to turn to the production of tobacco and sugar.

The secret of making cane sugar was introduced in Martinique by Dutch Jewish settlers driven from Brazil. The cultivation of sugar cane replaced that of tobacco in the Antilles and made Martinique prosperous in the 18th century. With the first cane juice distillation techniques, improved by Father Labat in 1694, the era of alcohol began.

Father Labat perfected the production process by inventing the still. Many sugar factories were then paired with a distillery. The French Antilles became engines of the development of sugar and rum production. The first sugar factories were born in Martinique, with capital provided by merchants from various ports of France and the Paris region.

The sugar industry developed rapidly: the number of sugar factories increased from 119 in 1671 to 456 in 1742. The areas cultivated with cane expanded while land concentration persisted. In total, more than half of the cultivated land belonged to large landowners, the future Békés (descendants of White colonials). Technical advances, such as mills, allowed for increased production.

The profitability of cane was also boosted by the production of exported raw molasses. For two centuries, sugar cane was exploited in Martinique. The banana appeared in 1730, but royal authorities had to impose it to keep it alive.

The French Antilles became engines of the development of sugar and rum production.

The cultivation of fruits and vegetables, bananas (which appeared in 1730 and were consumed as much as a fruit as a vegetable), and livestock farming were necessary for the subsistence of the population, particularly for feeding the slaves. However, despite warnings, obligations, and penalties, the settlers did not care much about feeding their slaves. They sought to discharge this obligation and ended up giving the slaves Saturdays to cultivate a piece of land for their own subsistence on the dwelling.

In 1787, a quarter of the land was cultivated for food. The development of crops necessitated the conquest of new lands. Little by little, the rest of the island was populated: Ducos from 1682, Le Lamentin in 1690, then the rest of the Atlantic coast (Le Robert in 1697, Le François in 1694, and finally Le Vauclin in 1720), and Le Gros-Morne, which specialized in cocoa production. The population grew from 23,362 inhabitants in 1701 to 74,042 in 1738, then to 89,300 in 1783.

Technological advances, such as mills, allowed increased production. The profitability of cane was also boosted by the production of exported raw molasses.

Thanks to the Exclusive system, which exploited them, the colonies created wealth for the metropolis, particularly for port cities like Nantes and Bordeaux, which benefited from direct trade with the islands (textiles, food products, raw materials such as construction materials and manufactured goods) and the triangular trade, i.e., the slave trade.

In addition, with the Exclusive prohibiting the islands from refining sugar, it was the merchants and refiners of the mainland who derived enormous profits. In 1789, France supplied half of the sugar consumed in Europe!

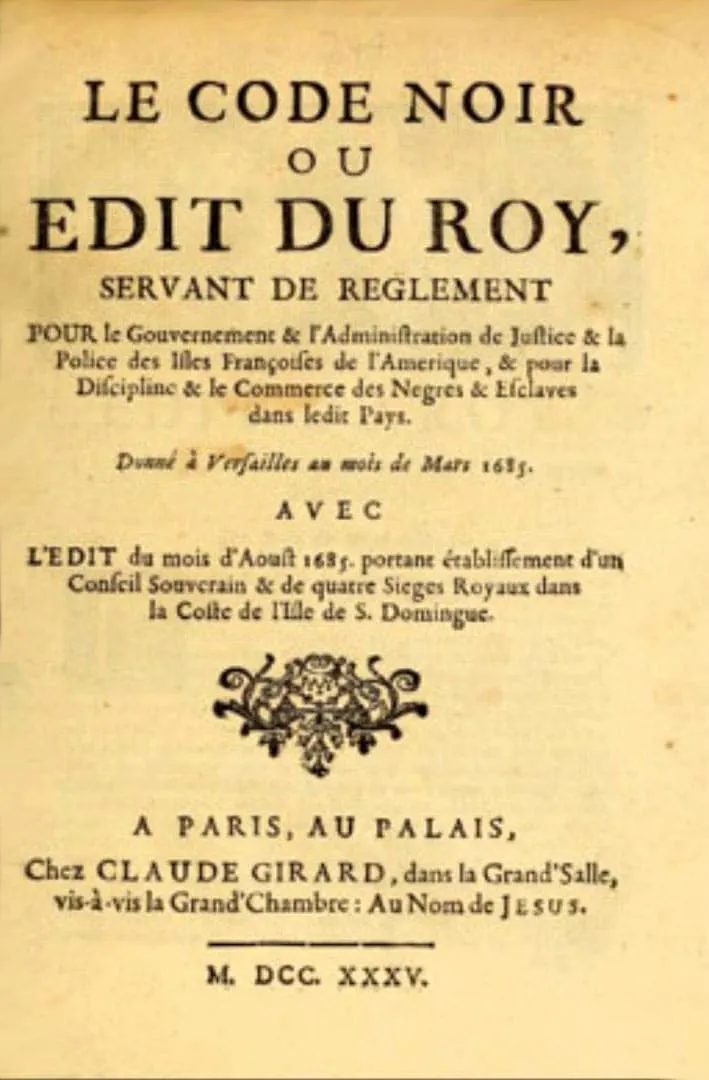

The Code Noir

Originally intended to prohibit the abuse and mistreatment of slaves on plantations and to suppress illegal trade between Africa and the West Indies, the Code Noir of 1685 ultimately became a text that regulated and institutionalized slavery.

In 1724, the revised version of the Code Noir formally legalized the practice of slavery in the French colonies. Enslaved Africans were housed in wooden huts on the expansive estates of their masters, to whom they were considered property and from whom they were expected to show unwavering obedience.

While men labored on the plantations, women were often assigned domestic roles within the homes of wealthy landowners. Their responsibilities included household chores as well as the care and informal education of settler children.

Under the Code Noir, masters were required to baptize and instruct their slaves in the Catholic faith. The law also sought to suppress births outside of marriage between enslaved women and free men. However, slaves were permitted to marry one another, lodge complaints about mistreatment, and save money to potentially purchase their freedom. Escape attempts were harshly punished if the fugitive was recaptured.

Enslaved individuals could be traded or sold to other owners. Although several slave revolts occurred in Martinique, none led to a significant change in the conditions endured by these servile populations. The system of slavery persisted on the island for nearly two centuries, until its abolition was officially decreed on May 22, 1848.

Political and institutional developments during slavery

In terms of local institutions, colonial administration was marked by the supremacy of military authority, which—due to France’s remoteness—concentrated all powers within itself. In 1674, the King reclaimed his prerogatives and established a unified military government for the Caribbean colonies, headquartered in Martinique.

Over the centuries, Martinique alternated between French and British control. During the French Revolution, several philosophers denounced the status of non-White populations in the colonies. Although the abolition of slavery was championed by some revolutionary figures, the British occupation of Martinique from 1794 to 1802 reinstated the Old Regime and its practices.

In other French colonies, the trajectory was different. Napoleon’s abolition and subsequent restoration of slavery contributed to the independence of the Republic of Haiti in 1804.

In Guadeloupe, British occupation in 1794 lasted only one year. The English were expelled by Victor Hugues, aided by formerly free or freed slaves. When Napoleon reinstated slavery in 1802, a revolt was led by Louis Delgrès—a free Black man born in Martinique—who, along with his companions, chose to “live free or die.”

Returned to France by the British, Martinique did not experience these revolutionary developments and continued to uphold slavery until 1848. On February 24 of that year, the July Monarchy was overthrown. François Arago, Minister of the Navy and Colonies, acknowledged the urgency of emancipation but preferred to defer the matter to the incoming government.

Thanks to the decisive intervention of Victor Schoelcher, Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, a series of decrees was issued on April 27, 1848. The first decree abolished slavery, with a two-month implementation period in the colonies. It also provided compensation to former slave owners.

At the same time in Martinique, tensions escalated. Violence broke out across the island as enslaved people, having learned of the developments in France, refused to wait. They rose in rebellion, and the uprisings in Saint-Pierre on May 22 and 23, 1848 proved decisive. Regardless of the original implementation timeline, the decrees were enforced immediately. On May 22, 1848, the Governor of Martinique officially proclaimed the abolition of slavery

From the end of slavery in the departmentalization

Since the end of slavery had been decided, settlers faced labor shortages. This intensified with the official proclamation of abolition. The newly enfranchised refused to work for their former masters and preferred to cultivate small plots of land acquired after their release. Settlers, therefore, sought quick solutions to obtain cheap labor willing to endure harsh working conditions.

They turned to Asia (India and China) and Africa (the Kongos). The Chinese, spared from field labor, adapted well to the local community and pursued trade. Indians, who arrived during this period under miserable conditions, often abandoned the fields or opted for repatriation to India after a few years.

Some newcomers adapted and integrated into the local population through marriage, including unions with Creole descendants of former slaves. These arrivals did not disrupt local life, and no significant inter-ethnic tensions were reported.

In 1898, Martinique had a population of approximately 175,000 inhabitants, including 150,000 Blacks and Mulattos (85%), 15,000 Indians (8.5%), and 10,000 Whites (5.7%). Contrary to common assumptions, the abolition of slavery in 1848 did not mark the end of labor importation to the island. Between 1853 and 1885, over 29,000 Africans were brought to Martinique under contract, with the promise of free return. These individuals came primarily from Central Africa—present-day Congo-Brazzaville, Congo-Kinshasa, and Gabon. Despite emancipation, Black populations remained in precarious conditions.

The Third Republic ushered in some progress, notably universal male suffrage and the establishment of compulsory, secular, and free public education in 1881. Nevertheless, the White descendants of slave-owning families, known as Békés, retained control over land and economic power. A new social class began to emerge: the Mulattoes, positioned between the White and Black communities. While not enjoying the full privileges of the former, they had more opportunities than the latter—especially in education, which enabled them to ascend the social ladder. Many accessed professions such as medicine and law, and held favorable positions in commerce.

A prevailing mindset during this period was encapsulated in the phrase chapé la po—a Creole expression meaning "escape the skin." For many women, this meant striving to have children with lighter skin, in hopes of escaping poverty and gaining social mobility. Traces of this mentality can still be observed today.

Martinique in the 20th century

One of the most striking events in Martinique’s 20th-century history was the eruption of Mount Pelée on May 8, 1902. This eruption reshuffled the island’s fate: Fort-de-France became the new capital, replacing Saint-Pierre, which was completely destroyed by the volcano’s pyroclastic surge. In the aftermath, Martinique faced numerous economic and social challenges. The sugar industry, once a pillar of the local economy, was severely weakened by competition from beet sugar produced in France and cheaper sugarcane from neighboring islands.

Aimé Césaire, a young Black Martinican, returned after completing his studies in France. He wrote several poems and books on the condition of Black people in the Caribbean, the most famous being Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal).

In 1946, he was elected mayor of Fort-de-France and became a member of parliament for Martinique. He denounced the corrupt and concentrated power of the Békés. While much of the world was engaged in movements for independence—such as in India, Indochina, and North Africa—Césaire believed that the best path for Martinique’s development and economic modernization was through deeper integration with France. He therefore supported the law of departmentalization, aiming to make Martinique a French department like those in mainland France, and no longer a colony.

On March 19, 1946, Martinique officially became a French department. Although this change in status helped stimulate economic development and allowed the island to receive aid from the European Union, the economic structure of Martinique remained largely unchanged. The Békés still hold the majority of the island’s economic power—owning 52% of the land—and continue to dominate key sectors such as supermarkets, banana plantations, and exports, car sales, and leasing.

Tensions remain palpable among the Black population, who are often relegated to secondary roles and whose living conditions are generally more modest than those of the descendants of former colonists.

Strikes and demonstrations broke out in 2009. The population denounced the high cost of living, elevated supermarket and fuel prices, and low wages. After 40 days of paralysis across public and private administrative services, an agreement was signed between the main unions, the state prefect, and local politicians.

Although the measures taken helped calm the revolt, they were temporary and are no longer in effect. Since the uprising known as the grève du 5 Février (February 5th strike), the situation in Martinique has remained calm, but no major issues have been resolved.

On January 1, 2016, Martinique became a Single Territorial Community, nearly 70 years after departmentalization. This reform ended the dual structure of the General Council and the Regional Council, consolidating their responsibilities into a single governing body.