West Indians are known to have "music in their skin" (Music in their skin means in French la musique dans la peau. It is the intro of Maldon, a song of the West Indian band Zouk Machine), and our theme here will not deny it. Martinique has seen the emergence of many artists who have considerably enriched the local music and even managed to be known on the international scene.

Thus, a small island unknown to a large number of inhabitants of this planet will reveal itself thanks to men and women who have valued this art. The current Martinique music, which resembles so much its population of today, namely mixed, was enriched as the years went by by Caribbean, European, African, and American influences without being detached from its base.

In the field of Caribbean music that has brought to the world the rhythms of salsa, merengué, bachata, reggae, dancehall, calyspo, soca, among others, Martinique has seen the birth of bèlè, chouval-bwa, damyé, biguine, mazurka, and, of course, more recently, zouk, dancehall, soca, among others.

The primordial role of music among the Amerindians

Yes, music was not only born in the 20th century with the contemporary rhythms that we know! At the time of the Arawaks/Tainos, music occupied a primordial place in life. It was at the heart of daily rituals. The latter had their own instruments and often danced during popular ceremonies.

They used music to remember and tell their stories, for celebrations and special events, to communicate with spirit guides, the zemis, to heal illnesses, to protect against spells, and to force the storms of Mother Nature.

The Arawak also used music to get rain when they needed good crops, to hunt, and to fish. Music was a primordial art, and one of the most beautiful gifts a Taino could give was a song.

However, we can only guess at the form of music of the Tainos because the Spanish chroniclers did not leave many details. It was generally very simple and monophonic, which means that it contained only one line that descended its tone.

There wasn't much harmony. There were often songs between a leader or soloist and a choir, which meant that the choir sang in the same melodic line. These same leaders sang a repetitive chorus.

Fray Ramón Pané, a Catalan monk of the Order of St. Jerome who accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage, was the first to study the Arawak language and wrote a book on Arawak civilization (Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios, Relation on the antiquities of the Indians). In it, he describes a percussion instrument called "mayohavau" that the Arawaks used during their religious rituals. It was made of fine wood and had the shape of an elongated calabash. It was up to one meter long and half a meter wide.

The sound produced by this instrument was heard over a distance of up to 7.5 m. This instrument was played by the chiefs of the tribe. It accompanied the songs, which were used to transmit customs and laws to younger generations.

The sound produced by this instrument could be heard over a distance of up to 7.5 m. This instrument was played by the leaders of the tribe. It accompanied songs that were used to pass on customs and laws to younger generations.

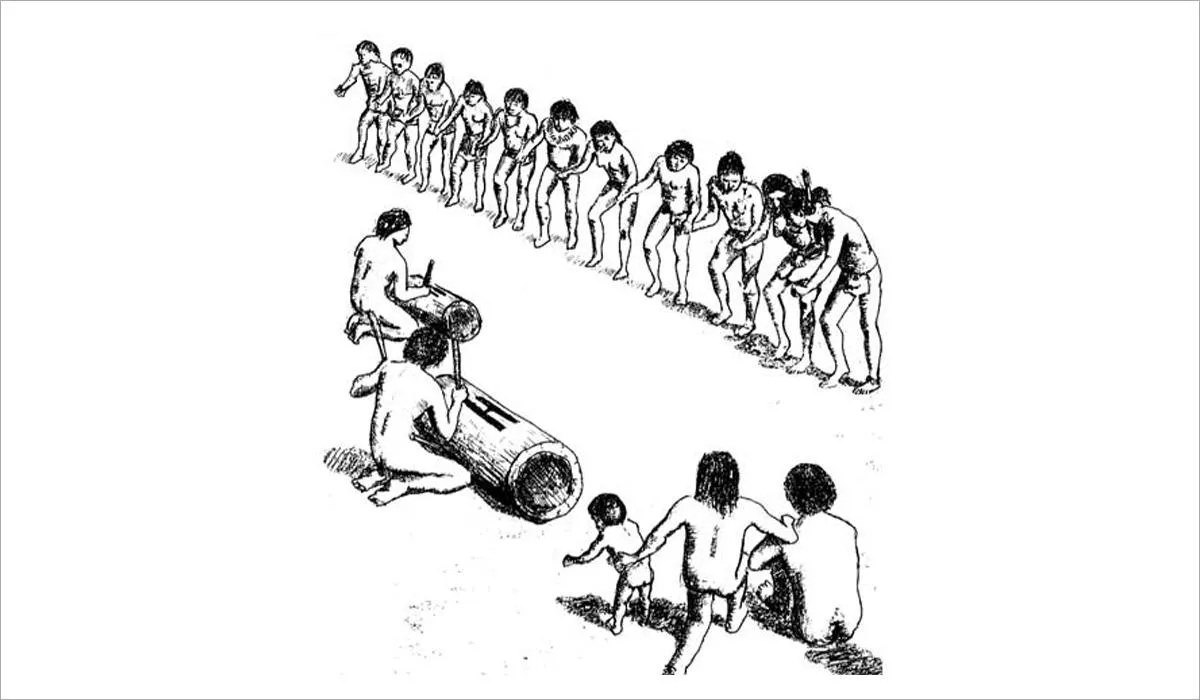

The mythological songs, "areitos", were sung while dancers, who could number up to a thousand, moved to the beat of a percussion instrument made from gourds, the güiros. The areitos were not only songs, they were also dances in a ceremony that could be described as socio-religious. Flutes, made of conches or reeds, were also visible during the musical celebrations, as well as the maracas (a kind of chacha), an instrument different from the one we see today.

These ceremonies were prohibited after the Spanish conquest. This caused the loss of most of the musical instruments and artifacts from the Arawak period. These survived the colonial period only by being hidden in caves and other hiding places in Puerto Rico for example.