Songs and dances

The importance of music

Sunday was the slaves' rest day; they had free time and could devote their time to whatever activity they wanted to do. Thus, they very often used this day to grow a small plot of land left at their disposal to plant fruits and vegetables for their personal consumption.

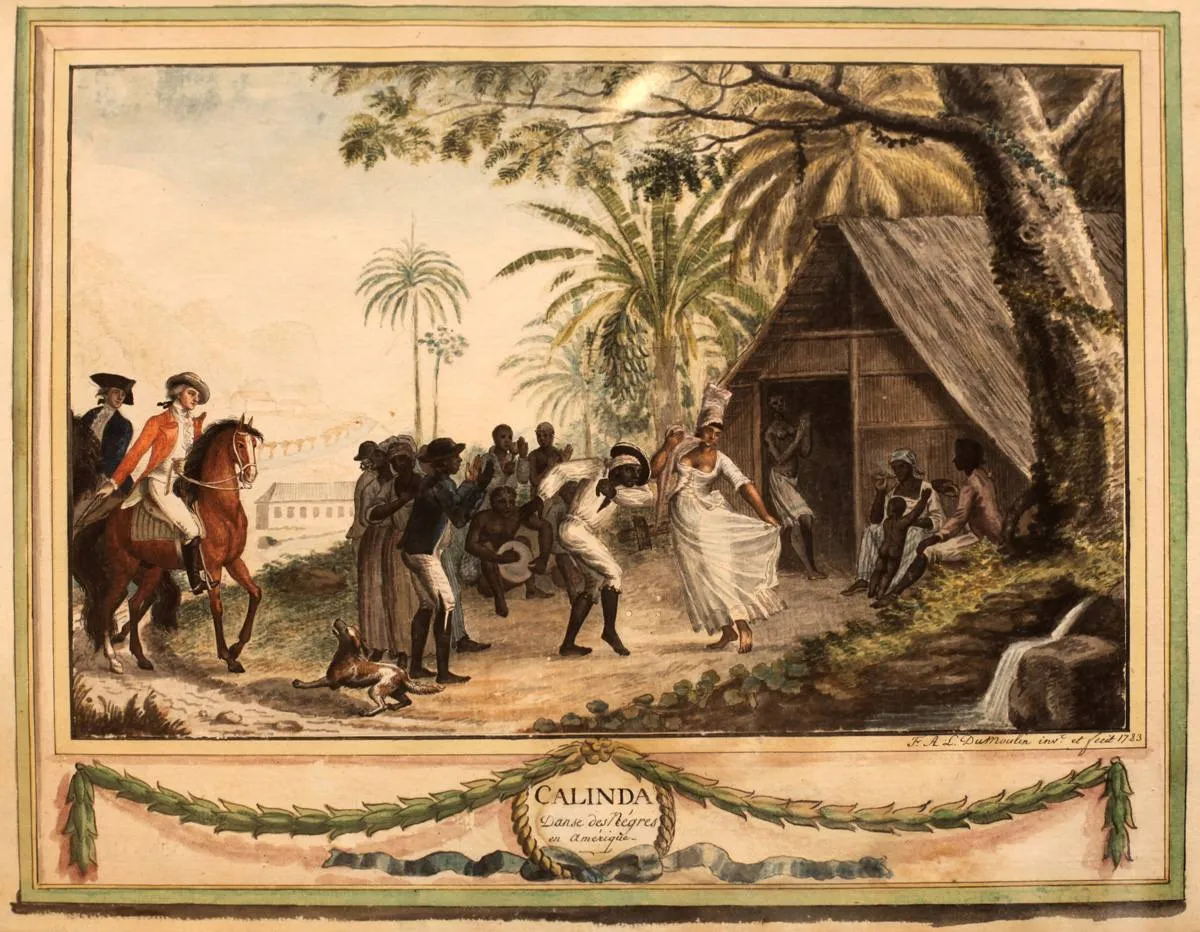

We know, however, that they also liked to meet in festive meetings where they sang and danced, as illustrated by the painting attributed to Augustin de Brunias (1730-1796), an Italian painter who died on the island of Dominica after having lived thirty years in the West Indies. These happy moments reminded them of their Africa, from which they had been torn to work on the plantations in the West Indies.

Usually, women did not play instruments. This task was most often reserved for men. The women were singing. To the choirs of one or two lead singers with bright voices, improvising songs answered other singers, dancers, drums, and other guitars.

Also, to describe the pronounced taste of slaves for music, Médéric Louis-Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry (1750-1819), a lawyer of Martinican origin, an active defender of slavery and close to the Enlightenment, writes that he is "So powerful that the negro, the most tired by work, always finds strength to dance."

The songs and the dances were present at every moment of the life of the slaves, particularly during the work of the fields, with the common dances of the men which one calls today "lasotè". Lasotè is a form of dance in which workers dig the ground by making a dance step with each beat of the drum.

Even in sadder times, like funeral ceremonies, music was present. The banza was out, as was the drum that sounded before everyone shared a common meal.

The dances

Regarding the dances, they were numerous, but they were often the same rhythms that we found from one island to another. One of the most famous dances of the period is the calenda. Calenda was a lively and lively dance found in North America and the Caribbean. It is called chica in Santo Domingo, congo in Cayenne, and fandango in Spain.

Depending on the location, her character is extremely voluptuous and lascivious. Two drums, made of hollow pieces of wood covered with a sheepskin or goatskin, accompanied the dancers, lined up in a circle.

On each drum is a straddling Negro, who hits it with the wrist and fingers, but slowly on one and rapidly on the other.

Other slaves simultaneously shook small calabashes filled with pebbles or corn seeds (ancestor of the maracas/chacha). The orchestra was sometimes supplemented by the banza.

The first person to have mentioned African dances in writings is Father Labat, who described them in Martinique in 1694 in one of his works:

The dancers, men and women form a circle and without moving they do not move nothing but lift their feet in the air and hit the ground with a sort of cadence, holding their bodies bent down to the ground, each facing each other.

These dances traveled from port to port during the period of slavery. They gave birth to other dances, the sarabande and the chaconne in Havana in the 16th and 17th centuries, the calenda and the bamboula in the 17th century, in the 18th century, the chica and the tango, then finally the mambo in the 19th century.

The British colonies prohibited these dances, so calenda and bamboula did not flourish in plantation societies in Virginia and Carolina. Likewise, they had banned African languages, religions, drumming, and even public meetings of slaves.

Another dance, voodoo, which was above all religious. The name of voodoo is applied by the "Negroes to a supernatural being" which they present in the form of a snake, of which a high priest or a high priestess interprets the wills. “Slaves often invoke him to ask him to rule the minds of their masters. They then engage in a kind of bacchanalia in which, overexcited by the spirits, they come to tremble violently, to bite each other, and finally to lose all feeling ”. It was in voodoo assemblies that plots were frequently hatched. Each slave took an oath not to reveal anything, under penalty of having to undergo a terrible punishment.

The dance at Don Pèdre, which dates from 1768, was more violent. “It was not uncommon to see Negroes falling dead, because they had drunk large quantities of tafia, mixed with crushed gunpowder."

Finally, there were what were called country dances.

The domestic negroes, imitators of the whites whom they like to ape, dance minuets, country dances, and it is a spectacle likely to cheer up the most serious face than that of such a ball where the oddity of European adjustments takes. a sometimes grotesque character.

The dances varied according to the origin of the slaves and their condition:

The Negroes of the Gold Coast, bellicose, bloodthirsty, accustomed to human sacrifices, only know fierce dances like them; while the Congos, the Senegalese and other Africans, shepherds or farmers, love dance as a relaxation, as a source of pleasure.

It should be noted that at the end of slavery, in very hierarchical societies and where African culture was marginalized, many newly freed people dropped these dances considered as belonging to slaves.

In “French Colonies. Immediate abolition of slavery", Victor Schoelcher recounts a scene:

In these countries riddled with prejudices, hierarchical from the first to the last level, everything that recalls servitude to the freed is odious, unbearable, repugnant to the not that the bamboula, this dance which the Negro loves with passion, he often ceases to indulge in it as soon as he is freed, because it belongs exclusively to the slaves. We saw a slave who had redeemed his daughter forbidding her bamboula as unworthy of a free woman. The poor child did not yet have the vanities of her condition and would have liked to become a slave again for an hour or two.